A New, New Orleans: Queer New Orleanians and Hurricane Katrina

In this Exhibit:

Hurricane Katrina was a Category 5 hurricane that struck New Orleans in August 2005. It is often considered one of the worst hurricanes to ever hit the United States.

Katrina started as a tropical depression near the Bahamas and officially became a hurricane two days later when it passed over Miami, causing the deaths of two people. It then continued over the Gulf of Mexico, where the warm waters caused it to strengthen. Prior to the storm hitting New Orleans, there was a mandatory evacuation issued. However, many residents stayed for a variety of reasons, including insufficient funds, no transportation, or advanced age.

Hurricane Katrina initially caused moderate damage, primarily from the nineteen-foot storm surge and strong winds. Directly after the storm, officials thought New Orleans had been spared the majority of the destruction due to the strongest winds hitting elsewhere. Later that morning, however, a levee broke, and the city started to flood. This initial flood overwhelmed other levees, and soon around 80% of the city was underwater.

The flooding hindered relief efforts stranding many in dangerous situations, causing many deaths. At the end of the storm, Katrina caused the deaths of around roughly 1,200 people and permanently displaced over 400,000 others. It also accrued $108 billion dollars in property damage, the most ever recorded in the US. Demographic shifts were exacerbated after the hurricane. Historically disenfranchised groups like lowest-income residents and families, as well as the African-American population, found it hardest to return and resettled elsewhere.

While Hurricane Katrina was a natural disaster that could not be predicted, hindsight reveals warning signs that could have prevented some of the devastation and loss of lives. The natural geography of New Orleans meant some parts of the city were below sea level and, therefore, prone to flooding. These areas were also more likely to be inhabited by low-income communities. New Orleans had previously had levees constructed to reduce flooding. Levees are walls that prevent waterways from flooding nearby areas. In 2006, a report by the Army Corps indicated that the levees were vulnerable to failure. During and after the storm, over 50 levees failed, and studies have revealed that the failed levees caused the worst impacts and deaths. (Gibbens)

Established in 1718, New Orleans’ lifestyle of entertainment immediately attracted many queer artists and creators. Throughout the 18th-, 19th-, and 20th- centuries, queer people built New Orleans’ culture, developing jazz and designing the infamous ironwork of the French Quarter (“Timeline of LGBT+ History in New Orleans”). The publicity generated by famous creators like Tennesse Williams, as well as the city’s liberal attitudes, continued to lure queer people (Herren and Willis). By 1933, the queer population of New Orleans was large enough to build Cafe Lafitte, the oldest queer bar in the US (“Timeline of LGBT+ History in New Orleans”).

While queer New Orleanians were not new, a distinct and proud culture established itself in the mid-century. Queer New Orleanians began to establish cultural institutions like the Fat Monday Luncheon (queer dinner), Krewe of Yuga (first queer Carnival parade), and the Steamboat Club (first queer social club) (“LGBTQ History in New Orleans”). All three of these establishments still operate today.

Like much of the country, New Orleans’ saw an increase in LGBTQ+ activism in the 1970s. Queer activism groups like the Gertrude Stein Society and the Tulane University Gay Student Union allowed queer New Orleanians new places to gather and speak up. This resulted in new events like a Gay-In at City Park, eventually becoming the city’s Pride Celebration (“Timeline of LGBT+ History in New Orleans”, “LGBTQ History in New Orleans”). They also established Southern Decadence, an ongoing event that crosses Mardi Gras with Pride.

More liberal than its other Southern neighbors, New Orleans was one of the first cities to give queer residents legal protections, receiving laws preventing discrimination in 1991 and 1997 (“LGBTQ History in New Orleans”). Unfortunately, like many minority groups, queer New Orleanians were decimated by Hurricane Katrina, even being blamed for the event (Haskell).

Today, the queer population of New Orleans is beginning to regrow and return to the “Lavender Lane” in the French Quarter. Even so, queer New Orleanians face many of the same problems other queer Americans face. In 2012, the last lesbian bar closed, worrying many about the future of queer spaces going forward (“Timeline of LGBT+ History in New Orleans”).

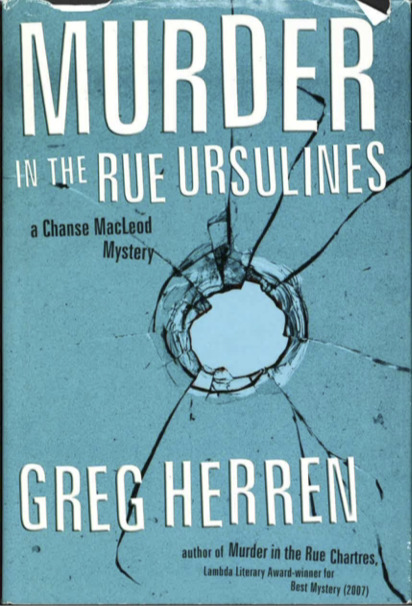

Case Study: Murder in the Rue Chartres and Murder in the Rue Ursulines

Murder in the Rue Chartres (Rue Chartres) and Murder in the Rue Ursulines (Rue Ursulines) are part of the larger Chanse MacLeod murder-mystery series. The series is set entirely in New Orleans and follows gay private detective Chanse MacLeod as he solves various mysteries. Murder in the Rue Chartres and Rue Ursulines are unique because they are set directly after Hurricane Katrina and discuss the effects of Katrina.

Rue Chartres focuses on Chanse MacLeod’s homecoming after evacuating from Katrina, only six weeks earlier. He struggles with survivor's guilt, as his house was left generally unscathed, compared to friends who lost it all, including their lives. New Orleans is still rebuilding as well, offering reminders of all the devastation. Even simple actions, such as driving across town bring back painful memories of the struggle to evacuate and the ensuing anxieties of not knowing when he will be able to return home or what his home will look like. These anxieties ultimately build into panic attacks, leaving Chanse struggling with spiraling thoughts. Rue Chartres also touches on how the city has responded to Katrina. When Chanse returns home, the city is struggling with looters and a large wave of crime. New Orleans is also under control by the National Guard, who set up a strict curfew, most likely to deter crime. Debris from the hurricane is still very evident and some parts of the city are a “dead zone,” with X’s remaining on houses.

Rue Ursulines is set a couple of years later. New Orleans has had more time to rebuild, but Katrina’s effects are still lingering. The effects are less obvious in New Orleans, with Rue Ursulines rarely talking about debris, destroyed houses, or closed businesses. In that aspect, the city almost seems back to regular business. However, Chanse is still struggling with the mental effects of the hurricane, with his panic attacks now being a symptom of PTSD. While his mental health has improved from Rue Chartres, Chanse continues to have panic attacks, a lasting effect of Hurricane Katrina.

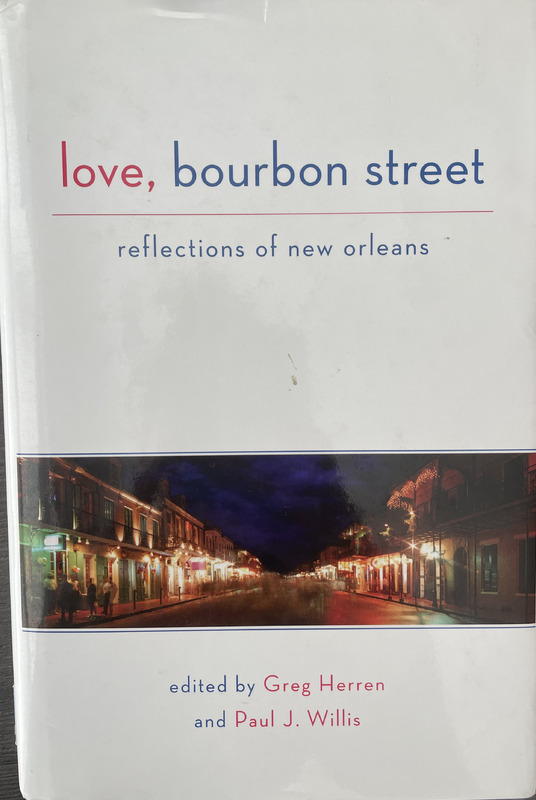

Case Study: Love, Bourbon Street

After the events of Hurricane Katrina, Alyson Books reached out to Greg Herren and Paul J. Willis, two queer New Orleanian writers and editors, about a publication that would bring awareness to the vibrant queer community destroyed in Katrina’s wake. The project, a collection of non-fiction essays and poems, Love, Bourbon Street details a myriad of queer writers’ ever-evolving relationship with the city of New Orleans.

The collection covers a vast quantity of time, with some writers imagining New Orleans back in Tennesse Williams’ day and some covering the rebuilding of the city post-hurricane. Although these pieces represent many different stages and perspectives of New Orleans, there are strong similarities between the works.

All the stories speak of an imperfect city — full of weirdos, con-artists, inequality, and dirt — but also one of hope and perseverance. Many of these essays paint New Orleans as a haven of acceptance and tolerance in the otherwise unwelcoming South Eastern United States. Many of the essays detail the writers’ coming out or queer awakening, something they credit to the atmosphere of tolerance in the city.

At the core of these essays, and the theme that truly binds them, is the persistent hope of the city and its residents. Although the city morale was destroyed (one essayist compares the city to ground zero during 9/11), and many, mainly impoverished areas, were completely decimated, the essays profess faith in rebuilding (81-92).

Most of this hope takes on a queer angle, with the writers explaining they came to New Orleans in their hour of need and were allowed to be themselves. Now that the city needed them, it was their duty to repay the favor. For others, there was no other place within the South Eastern United States they felt safe moving to, and would stubbornly resort to rebuilding to reassert their claims to live safely and proudly within the Deep South.

Love, Bourbon Street offers a unique insight into the perspectives of queer New Orleanians and their struggles and triumphs within the city. While not perfect — none of the writers ever claim it to be — New Orleans is the shelter for weirdness they all call home (Herren and Willis).

Importance of Queer New Orleans in the 2000s

For this exhibit, we assembled a collection of Alyson Books that mentioned or were based on Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and its surrounding area. We’ve presented them in a carousel for easy discovery and viewing.

Underneath this carousel, we’ve outlined the necessary context to understand queer New Orleans and its cultural contexts for the early 2000s. We’ve followed this with a more in-depth discussion of three books published by Alyson Books after Hurricane Katrina. This will allow visitors to find in-depth examples of queer writings on Katrina without dedicating the time and effort to acquire and read them. Finally, we included a curatorial statement to explain why and how we produced this exhibit and synthesize multiple aspects of our exhibit, bringing all our ideas together.

We thought of the idea to highlight New Orleans after noticing many of the books were set in New Orleans or had some tie to the city. One of our books was set after Hurricane Katrina, which started a discussion about creating our final exhibit on Katrina’s impact on New Orleans.

We then started researching the city and discovered that it was overlooked as both a queer hub and the site of a devastating hurricane. With this as our inspiration, we decided to discuss the ways queer New Orleans was impacted by Hurricane Katrina.

To build out our exhibit, we used the texts discussed in class to identify certain series and authors who discussed the subject. Then we identified other texts via tags and book summaries in this site’s metadata. From those texts, we selected three — two fiction and one nonfiction — to use as a case study to demonstrate what was occurring within the texts.

A Final Note

This project stemmed from a curiosity regarding the importance of New Orleans and the queer community. Multiple Alyson books we researched mentioned New Orleans, and we were surprised by this prominence. Compared to New York or San Francisco, New Orleans is overshadowed. Its location in the Deep South and the relative size of the city has reduced its prominence in wider media as an important queer center.

Our exhibit seeks to highlight New Orleans, its queer history, and its devastation from Hurricane Katrina. Alyson Books featured these topics prominently in the mid-2000s, and we hope to continue their efforts of raising awareness for this vibrant city.

Like the city’s importance to Southern queer folk, the effects of Hurricane Katrina are also overlooked in terms of wider media representation. “Sexuality and Natural Disaster: Challenges of LGBT communities facing Hurricane Katrina” details the challenges queer New Orleanians faced.

Similar to many other minorities, the queer community was disproportionately affected by Katrina. This effect could be compounded if they were not white, assigned male at birth, or affluent. Due to the lack of recognition for queer unions, queer couples were denied governmental aid. Displaced queer people were also more likely to be targets of police violence. Finally, queer New Orleanians were blamed for Katrina by religious conservatives. These extremists claimed Katrina represented God’s wrath against queer communities, adding additional hardship to queer folk’s rebuilding process.

Although no hate crimes were reported by “Sexuality and Natural Disaster,” it does state that the situation was ripe for such actions. While we cannot state for certain such crimes occurred, it is likely they happened but went unreported or were incorrectly labeled.

With this disproportionate impact, it was important we covered both sides of the queer New Orleanian experience— both deserving more attention and representation. While LGBTQ+ history in New Orleans can be vibrant and joyful, it is equally important to remember these dark times, especially as the city is still recovering from Katrina twenty years later.

We hope our exhibit brings new light and appreciation to New Orleans and the queer people who call her home.

Works Cited

Gibbens, Sarah. “Hurricane Katrina Facts and Information.” National Geographic, 16 Jan. 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/hurricane-katrina.

Herren, Greg, and Paul J. Willis, editors. Love, Bourbon Street, Alyson Books, 2006.

“LGBTQ History in New Orleans.” New Orleans Tourism Board, https://www.neworleans.com/things-to-do/lgbt/history/.

“Timeline of LGBT+ History in New Orleans.” The LGBT+ Archive Project of Lousiana, https://lgbtarchiveslouisiana.org/timeline-of-lgbt-history-in-new-orleans/.